1.5 Gen Testimonios: Why I do this Work | Alejandra Mejía

Sociologist Rubén G. Rumbaut coined the term “1.5 generation” to describe the experiences of immigrants who move to the United States between the ages of 6 and 12. These immigrants, like myself, have had formative experiences in both their home and host nations and have unique educational, occupational, linguistic, and social experiences as well as a distinct connection to the concept of belonging.

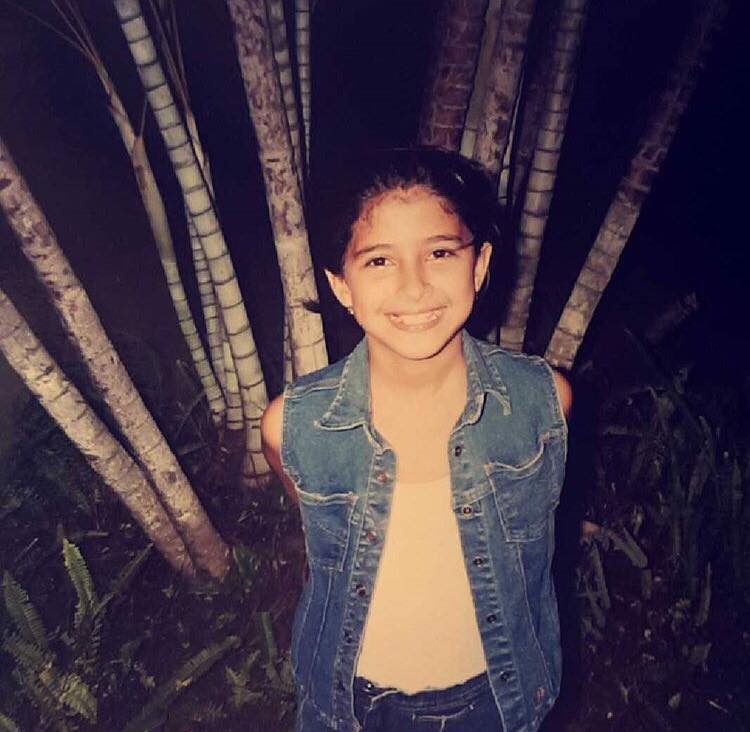

When I first stumbled upon the term “1.5 generation immigrant” in college, I felt like it more closely captured my experience, rather than first or second generation immigrant labels. The deep disconnect I felt from all the nations which I belong to: at birth, Honduras, Panamá until age 11, and then the United States. Holding this in-between identity has allowed me to develop a distinct and critical understanding of global migration and a commitment to the work of Migrant Roots Media (MRM).

My grandmother, mother, and I in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

Growing up a 1.5 generation immigrant was a tumultuous experience. As a young child raised in Latin America, I internalized the American Dream narrative in large part because of the media I consumed. It constructed an image of American exceptionalism. Over time, however, I have personally witnessed the harmful effects of global U.S. exceptionalism abroad and anti-migrant discourse in the United States, two related forces.

My older brother, mother, and I in Panamá City, Panamá.

Harmful narratives about migrants continue to circulate in the United States and MRM seeks to intervene in this dialogue by showcasing real stories of migrants. Mainstream narratives from all sides of the political spectrum are rarely told from the voices of migrants themselves. Politicians often criminalize migrants and focus on the negative economic effects of migration, such as native unemployment, and positive stories center narratives of successful integration. MRM explores the emotional and psychological battles faced daily by migrants and contextualizes the social, political, economic, and cultural realities of Latin America at different points in history. These stories appeal to human connection but, perhaps more importantly, point to the real causes of Latin American migration: U.S. imperialism in the Global South.

In Panamá, American control over the Panamá Canal lasted until December 31, 1999. While in control, Americans denied Panamanians access to the Panamá Canal Zone unless one worked there and, many times, natives performed menial jobs such as cooking, washing uniforms, and cleaning boots. It was not until January 9, 1964 when the lives of students were taken in anti-American riots for Panamanian sovereignty that the United States began working toward transferring control of the Canal to Panamá. As a result, U.S. imperialism has left lasting economic and environmental effects as well as tensions between Panamanians and Americans. These consequences led my single mother of two who was struggling to find a job in Panamá to migrate to the United States: a nation operating on a reductive, dichotomous understanding of migration.

My family’s journey in the United States has not been easy. As mixed-status, working-class immigrants, we have been relegated to second-class citizenship. I have been made aware, in my schooling and work experiences, how race, class, sexuality, gender, and citizenship status among other markers of difference are deeply ingrained ideologies that affect people’s experiences in navigating these spaces. Because of privileges I hold, including my lighter complexion and “good” English, I have been given access to spaces that many people in my communities have not. It is with this conscious awareness that I choose not to comfortably settle into the fully-assimilated American Dream narrative and, much less, the violent anti-immigrant discourse voiced by the current administration. Through MRM, we are making a conscious effort and commitment to explore and reveal the history of U.S. imperialism in Latin America and, consequently, contextualize immigrant experiences in this nation.

My subsequent article will further explore the history and effects of U.S. imperialism in Latin America.

*This article has been redacted to use the word “migrant” instead of “immigrant” in some cases to acknowledge different types of movement patterns.

Alejandra Mejía is the Chief Editor of Migrant Roots Media. She is also an Assistant Editor at Duke University Press, where she acquires books in Latinx history. Her politics and devotion to migrant justice are largely informed by her lived experiences as a working-class Central American immigrant in the United States.