Made in USA: Images of Incarcerated Mareros Perpetuate Fear of Migrants Amidst COVID-19

Disturbing photographs of incarcerated mareros in Izalco, one of El Salvador’s high-security prisons, have emerged in the last couple of days since the announcement of a 24-hour prison lockdown with enforced security measures. The images were released by the office of President Nayib Bukele after he announced a national state of emergency last Friday, April 24, following 23 gang-related murders reported to have happened in a single day and more than 70 over the course of the weekend. The state officials and media suspect the murders were orchestrated by gang members from inside the prisons. In the images, the men, who are close-shaven, stripped down to their boxers, and many tattooed on the head, face, and chest, are captured sitting only inches apart, their hands cuffed and heads bowed down. Few of the men wear protective masks as officers patrol them, protected with both masks and shields. Partly an intimidation tactic geared towards mareros and largely a publicity campaign on behalf of Bukele’s zero-tolerance government, the release of the photographs have garnered international media attention.

Image via Al Jazeera

Recent coverage by Al Jazeera, The Washington Post, and BBC News points to the obvious human rights abuses exacerbated during this emergent crackdown, which multiplies the health risks that the incarcerated men face due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Presenting these shocking images without historical context of gang violence in El Salvador, however, promotes the idea that we should only care about these men and the Salvadoran government’s “authoritarian” response because of the unprecedented pandemic, absolving the structural forces and actors that are truly responsible for both the gang violence and repressive state response from blame. What these mainstream media sources fail to acknowledge is that the gang violence rampant in El Salvador was, in many ways, made by and in the United States and that the sensationalization of images like these perpetuates fear of migrants and the image of Latin America as uncivilized.

Screenshot of AJ+ Instagram post, published on April 27, 2020

La Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18, two of Latin America’s most infamous street gangs, originated in Los Angeles in the 1980s and were exported to Central America via the U.S. deportation machine. The gangs’ origins coincide with the start of the Salvadoran Civil War (1980-1992), whose primary actors were the Marxist-Leninist guerilla group known as the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and the heavily U.S.-supported, repressive military government of El Salvador. Waves of Salvadorans were forcibly displaced from their communities throughout the course of the war, many fled to Los Angeles to escape violence, poverty, and instability. These conditions were largely created by the United States, which provided training, secret intelligence, and “hundreds of millions of dollars in economic and military aid” to the Salvadoran military and right-wing death squads. This was done in order to suppress any challenge to U.S. power during the Cold War. In the process, these U.S.-backed forces were responsible for the murders and disappearances of many union and community organizers as well as civilians suspected to be FMLN sympathizers, including Archbishop Óscar Romero, an outspoken advocate for social justice and the poor.

Once in the United States, these new migrants with precarious legal statuses faced physical violence (such as over-policing, criminalization, mass incarceration, and increased deportations) and the symbolic violence of shame and internalized oppression. These conditions were the grounds where many, mostly migrant men, started to look for a place of belonging, safety, and economic security in gangs. While small gangs existed in El Salvador well before the 1980s, as Elana Zilberg notes in Space of Detention (2011), what the physical space of Los Angeles did for the maras was to consolidate these various groups into a “broad-based confederation of cliques” associated with either of the two rival gangs, MS-13 or Barrio 18.

If we do not contextualize and interrogate the root causes of this violence, the suffering and transnational cycles of violence will never end. Al Jazeera speaks of the “unruly prisons,” which are so under-budgeted that inmates have little access to soap and water and are so corrupt that guards are intimidated to collaborate with prisoners. The Washington Post reports that “criminals took advantage” of the situation while police were focused on COVID-19 enforcement. BBC News ends with the note that Bukele has been “popular among citizens who have suffered from gang violence for decades,” but no one points to the historical source of this violence and the forces that continue to perpetuate it. The images of mareros in Izalco leave viewers with a bleak portrayal: what we have been socialized to think of as “dangerous gangbangers” in a dehumanizing position, made vulnerable by a deadly virus. What is the media’s role and accountability in reporting these stories?

Image via Al Jazeera

Screenshot of Daniel Alvarenaga’s tweet, published on April 27, 2020

Daniel Alvarenga, the son of Salvadoran war refugees and a video producer at AJ+, recently tweeted that “the war on maras is a business,” and that Bukele profits off of chronic poverty and gang violence, which justifies continued flows of money into the country through “U.S.-aid and ‘security’ spending.” Bukele, who has been likened to Donald Trump and supported by the U.S. government, has “promised limited government [and] positioned private foreign investment as the motor of development,” shifting El Salvador’s foreign policy sharply right since taking office. He has stated that El Salvador is to blame for the migrant crisis and the deaths of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his 23-month-old daughter, Angie Valeria (and countless other migrants) at the border, publicly absolving the United States from its role in forced displacements.

As someone who was born in Honduras, one of the countries at the heart of the Northern Triangle crisis, I ask myself: How do we shift our collective narratives to center those of people most directly impacted by structural violence? Decontextualized images and news stories serve the purpose of demonization of migrants and absolve from blame the broader structures and individual actors who create and willingly continue to perpetuate (and profit off) this violence.

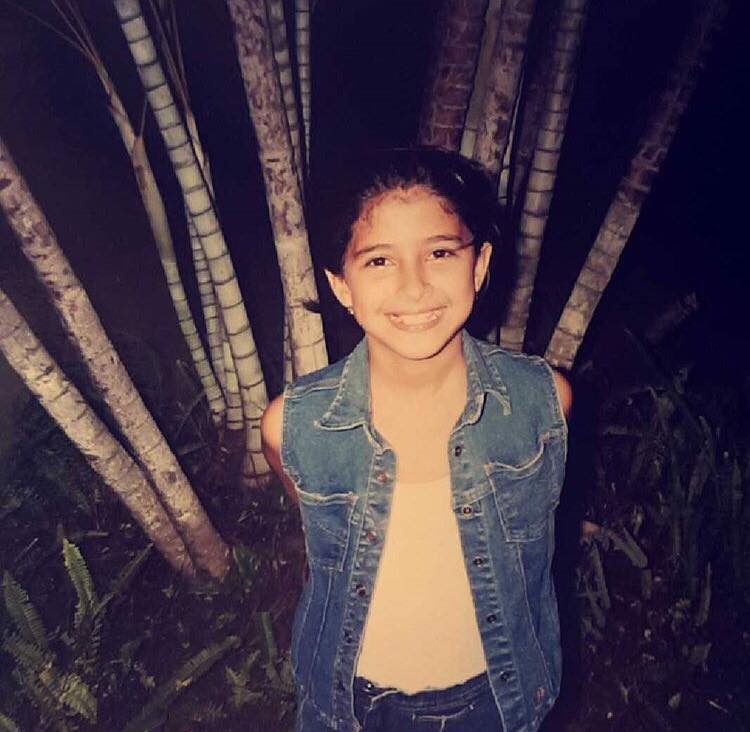

Alejandra Mejía is the Chief Editor of Migrant Roots Media. She is also an Assistant Editor at Duke University Press, where she acquires books in Latinx history. Her politics and devotion to migrant justice are largely informed by her lived experiences as a working-class Central American immigrant in the United States.