The Plunder of Mexico and My Journey as an Undocumented, Anti-Imperialist Organizer

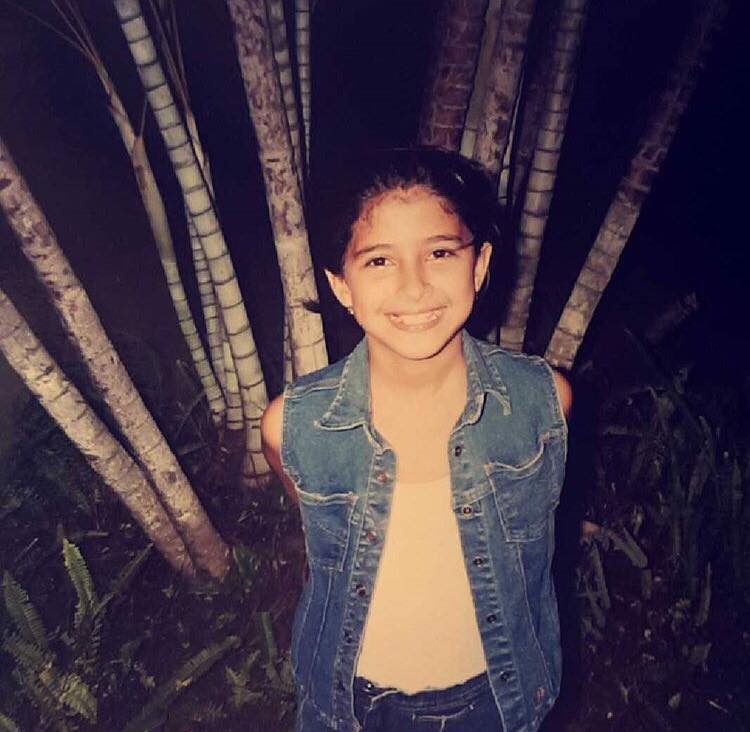

Victor, 5 years old, Atlanta, GA.

The story of my journey to the United States across the Mexican desert parallels the experiences of many migrants, yet each one of us comes to this country with our own unique stories that do not always get the chance to be told. What we do share in common, however, are the experiences of having lived through systems that pushed us out of our homelands.

During my high school years, my parents and other members of our community tended to give vague answers about economic crisis, poverty, and debt to my questioning of why they decided to migrate. As my political awareness developed during college, these explanations grew unsatisfactory. While economic hardships were indeed factors for their migration, I realized that they had underlying causes which were hardly ever discussed or understood. I began to more deeply question the root cause of my family’s poverty, my parents’ crippling debt which led them to bankruptcy, and the prevalence of unemployment and low-wage jobs in Mexico. For my undergraduate senior thesis, entitled “The Consequences of Neoliberalism in Mexico: Revolt, Migration and A New Mexico,” I set out to investigate these questions, and my findings profoundly reshaped my understanding of Latin American migration.

Through my research, I learned that the neoliberal economic policies that plagued Latin America from the 1980s to the present led to the impoverishment of the working and rural classes, laying the groundwork for the current “crisis” of migration.

Victor’s father, Mauro, Mexico.

My own family experienced the effects of these policies. In the late 90s, my father lost his job after the company he worked for, Gamesa, was privatized by the American company PepsiCo. Without the benefits his job provided, he accumulated debt to provide for us. This has been a common occurrence for millions of working-class Mexicans who have fallen victim to neoliberal policies that prioritize profit over livelihoods. After failing to achieve adequate employment, my father decided to embark on the dangerous journey across the border to the United States in 2003. He had no intention of staying in the United States and only planned on sending remittances back to us for a couple of years. However, he quickly learned that the “American Dream” was not what it promised. In 2005, due to the economic difficulties in the United States, my parents faced home foreclosure in Mexico. That’s when my mother, who had been managing a small store from our home while taking care of my brother and I, decided to bring us to the United States. I arrived in the United States at the age of four, accompanied by my nine-year-old brother and my courageous 34-year-old mother.

Victor with his older brother, Aldo, and their mother, Esperanza, Mexico 2004.

Vague memories and stories told by my family paint a picture of our journey as an uncertain, fearful, and traumatic experience. When reflecting on our journey with my mother, she remembers it as, “A difficult experience, mainly because I had my two small children with me. When we got to Phoenix, Arizona, we were robbed by our coyote who demanded more money and there was a chance that we had to turn ourselves in to the authorities because we were abandoned. I thought to myself, if we had been caught and sent back, I would not have tried to cross again. I could never put my children through that experience again. Compared to other migrants, our journey wasn’t that hard. But to see my children, who had such confidence in me and felt protected by me, in those moments, to be truthful, I felt completely powerless if something had happened to my kids. There were snakes, tarantulas, scorpions, and so many other dangers in the desert. If any of us had gotten hurt, we would have been left behind. How could I protect my children from all these dangers? Reflecting back now, I can say for certain that I would never expose my children to that kind of danger again.”

In Eduardo Galeano’s seminal work on Latin American political economy, Open Veins of Latin America, he captures the exploitation of the people by declaring:

“Latin America is the region of open veins. Everything from the discovery until our times, has always been transmuted into European—or later—United States—capital, and as such has accumulated on distant centers of power. Everything: the soil, its fruits, and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their capacity to work and to consume, natural resources and human resources (2).”

Even though Open Veins was published in 1971, Galeano’s words still resonate profoundly in 2023. The privatization of Mexico’s industries at the hands of American multinational companies created the conditions for mass displacement, most notably when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect in 1994. NAFTA opened over 91% of Mexican industries to foreign privatization. NAFTA’s primary objectives were to provide cheap labor for manufacturers and remove barriers to the flow and mobility of capital. Designed as an export-oriented strategy, NAFTA perpetuated Mexico’s status as a semi-peripheral nation, leading to declining wages, economic stagnation, a growing job deficit, and a surge in migration. The plunder of resources and labor in the agricultural, manufacturing, energy, and service sectors led to millions of refugees escaping poverty, unemployment, inflation, and violence.

Recognizing that 500 years of exploitation in Latin America are the root causes of the so-called immigration “crisis” is the first step in solving it. Moving beyond oversimplified narratives that scapegoat migrants and embracing a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of migration within a historical context is essential for meaningful progress.

Strengthening my anti-imperialist analysis as an undocumented organizer has allowed me to look deeply into my own story of migration and identify the need to shift discourse on (im)migration to truly address the root causes of displacement.

Victor Urquiza (he/him) was born in Michoacan, Mexico, and migrated to Atlanta, Georgia in 2005 at the age of four. He graduated from Delaware State University in 2023 and has aspirations of becoming a professor of political science. Victor’s dedication to fighting for immigrants, workers, and oppressed people stems from witnessing his parent’s exploitation as undocumented workers. He is an organizer with the Party for Socialism and Liberation and a workers’ rights organizer with United for a Fair Economy. Victor is an avid reader and writer who is currently working on publishing more articles on politics, history, and philosophy. He hopes to use his writing as a weapon to liberate and educate.

To keep updated with his work, follow Victor at https://medium.com/@urquiza.victor09