In the Presence of Absence | Jonathon Burne-Espinoza

“The one thing you have to understand is - growing up, the U.S. was everything to us.”

For most of my life, I didn’t understand this. Well, more specifically, I didn’t take the time to ask. My mother and I never talked about why she migrated to the United States, how she came to understand the myth of “the American Dream” as a tool of U.S. imperialism, or what her life was like in Honduras before she left with no intention of going back.

Of course, her experiences as an Afro-Honduran immigrant shaped my entire life story, even if I didn’t fully understand how. Our family, like many other Black and Brown immigrant families, struggles with the material poverty that the U.S. colonial state reserves for those it has displaced from their lands in its conquest for resources.

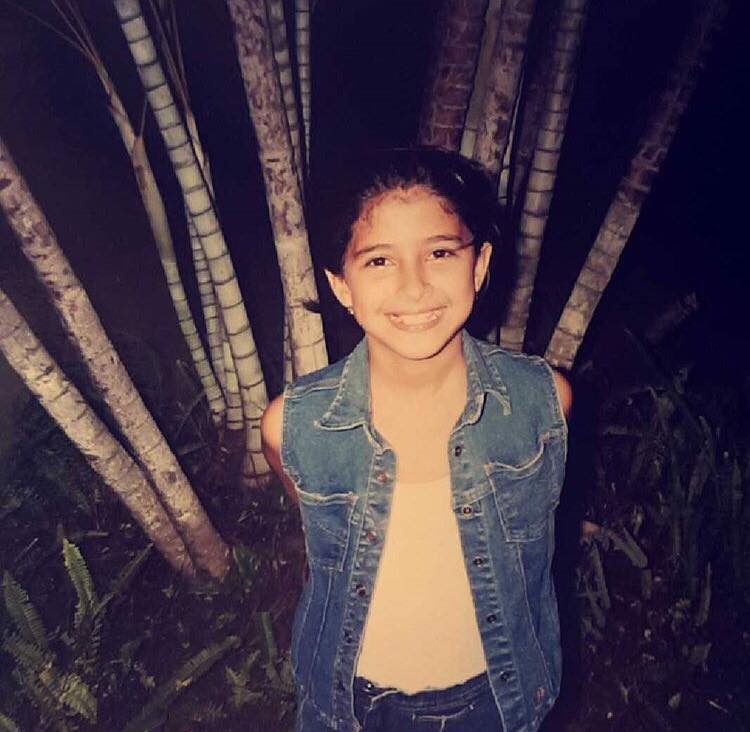

My mother and her four siblings during a family reunion.

Our family also struggles with another violent legacy of settler colonialism: a cultural poverty, a theft of one’s connection to their ancestral history. I didn’t grow up identifying with la cultura hondureña de mi mamá, partly because my mom was taught that “assimilating” and surviving in the United States required becoming more “American” - presumed to be more white, English-speaking, Christian, capitalist - and, partly, because I grew up with my dad’s white American family of Irish descent. Maybe because I present as racially ambiguous, or because my dad was also detached from his own cultural background, my connection to my Irish identity is less felt - but my inability to even understand my mother’s first language has always left me feeling empty, isolated, and wandering.

As my political consciousness grows by studying and practicing decolonization, so too does my understanding of this emptiness, and my ability to articulate it in the context of my mother’s story of migration.

I realize now that my former lack of interest in my mom’s background is a product of this cultural theft; that my identity is intrinsically tied to the historical erasure of languages, traditions, relationships to land, and ways of understanding the world; and that this violent erasure continues.

I imagine that somewhere, there are vibrant, colorful, endless threads connecting my life to the tapestry of my ancestors, threads that could intertwine a deeper understanding of who I am had they not been bleached and weakened before I was born.

And I hope that relocating myself in my mother’s history will help me find these threads and stitch together the tears, the wounds in the tapestry that have been veiled too long by white supremacy and intergenerational trauma.

The beginning of this journey is a question, for her: why did you come here?

~~~~~~~~

“The one thing you have to understand is - growing up, the U.S. was everything to us.”

Sitting with me outside of an overpriced coffee shop, my mom recalls her mother, a white hondureña from a relatively middle-class background, describing the wonders of “the American Dream” to her as a child. For my grandmother, los Estados Unidos was simultaneously a dream and an expectation of something greater than wealth: social status, respectability, and stability. These myths are what the United States promised mi abuelita, who would hire domestic workers in Honduras to maintain the illusion of affluence even if the family was struggling financially.

This aspiration to affluence is itself a legacy of European settler colonialism. It is rooted in mirroring the beliefs, lifestyle, and social relations of the colonizer. In most of the land that is now known as Latin America, the conquistadores violently supplanted Indigenous cultures with their own white Spanish culture. They colonized not just land, but also identity in their attempts to minimize collective resistance against their conquest. A recognition of this history of colonization is now being used as a tool for liberation among Indigenous and formerly enslaved communities to resist the learned aspiration to whiteness that was forced upon our ancestors.

After a brief silence and a few sips of coffee, my mom tells me that when she was a teenager, my grandmother decided to send her to Los Angeles to finish high school even though she couldn’t speak any English. This was during the 1970’s, almost 70 years after Theodore Roosevelt “declared the U.S.’s right to exercise an ‘international police power’ in Latin America.” I wonder if mi abuelita sensed that the instability created by this intervention in Honduras would soon become the catalyst for massive displacement throughout the region. I also wonder if, in another world free of these histories of exploitation, she would have even considered sending her daughter away.

My mom’s experience upon arrival was traumatizing. She internalized profound shame about being “different” - her accent, her dark skin, and her thick curly hair set her apart from both her family and friends. Attempting to become “American” was a painful process. In her struggle to assimilate, she turned to drugs and narcotics to deal with the psychological toll. Struggles with mental health, rooted in the social isolation and material scarcity associated with displacement, characterized a large part of her transition to life in the United States.

At this point in the conversation with my mother, I’m beginning to identify some of the threads connecting our tapestry together. I’m reflecting on how I also don’t look like my siblings or my parents, and have consistently felt othered in the various communities I’ve been part of, either because of my multicultural background, political beliefs, spirituality, or non-binary identity, which have produced a unique type of isolation that I hear her describing. I tell her, “I’ve always thought that if I spoke Spanish growing up, or if I grew up knowing other people who know what it feels like to be ni de aquí, ni de allá, I would feel like less of an outsider all the time.”

After a short pause and the last taste of coffee, she responds:

“The problem is that, when your dad and I divorced, when you were really young like three or four, you went to live with your dad’s parents. I wasn’t given the opportunity to raise you in that way. And by the time that I did get custody of you when you were a bit older, you didn’t really seem interested in the things I would do to stay connected to my roots, like the Honduran food I would cook. It’s so funny, I remember one day when I picked you up from elementary school, you were so upset because somebody on the playground had called somebody else ‘white trash.’ I asked you why you were so upset, and you said, ‘Because that person was white, like us!’ You already had this idea about who you were, about who your family was, and I didn’t have much control over that.”

Looking down at her empty cup, my mom continues:

“But also, I think I still had some shame about speaking Spanish and coming from where I come from.”

Another thread, and the one that I feel most acutely: U.S. cultural imperialism has robbed us both of our cultural identities. The visceral awareness of lacking, the presence of absence (a phrase borrowed from the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish) which transcends time and space, spans across peoples who have had their lands, communities, bodies, and spirits stolen, commodified, and repackaged back to them disfigured in the rhetoric of diversity, humanitarianism, and progress.

My mother and I at my high school graduation.

I wanted to hold that moment. I wanted to unravel all the harm, the trauma that was loaded into every word of that sentence. We had identified a tear in the tapestry, we’d even located the individual threads that had been worn thin, almost invisible, by generations of calculated historical erasure. But I didn’t have the words yet, or maybe I did, and I just didn’t know how to put them together.

On the walk back from the cafe, my mom tells me that she eventually found a sense of belonging through a deeper reflection on her identity as a “Latina” in the United States. Her interactions with the criminal justice and immigration systems in this country made her realize that, as an Afro-hondureña, she was unfairly criminalized and racialized. She eventually formed community with other women who had been othered in similar ways because of their bodies, mental health struggles, and legal status.

I’m hoping that by recovering my tapestry, finding my place in it alongside the weavings of those before me, and interlacing mine in beautifully transformative spaces such as Migrant Roots Media, I will further my own process of belonging.

Jonathon Burne-Espinoza was born in Los Angeles, California to an Afro-Honduran mother and an Irish-descendant father. Currently based in Brooklyn, New York, Jonathon is working in public interest immigration law where they are learning how to be an effective migrant justice organizer. Jonathon is passionate about connecting creative expression and political organizing between revolutionary movements, and is committed to liberatory education amongst oppressed groups throughout the world. They are an aspiring poet and musician.