We are failing our immigrant communities: COVID-19 and the impact on remittances

The coronavirus has torn at the very fabric of transnational communities, most clearly demonstrated by the significant drop in remittances.

Since migrating to Los Angeles in 2001, Lilian, a Salvadoran immigrant worker, has been a loyal customer at her neighborhood’s money transfer store in the Westlake District. Like many immigrants, she continues to support her family in El Salvador by sending remittances— money sent to the ancestral homeland by an individual living abroad. Until recently, what had become a monthly routine for Lilian—send money at least once a month, call her family to share the 8-digit reference number, and wait for their call to confirm that the money was received —was suddenly disrupted from one day to the next. The loss of jobs and the increase in financial insecurity during the coronavirus pandemic caused immigrant families like Lilian’s to send less money back to their countries of origin.

In early March, burgeoning cases of the novel COVID-19 prompted Governors across the U.S. to declare a State of Emergency to prepare for and contain the spread of the virus. Within days of the first positive case in California, Governor Newson and Mayor Garcetti of Los Angeles followed suit and issued a “Safer at Home” emergency order, calling on residents to limit non-essential activities outside of their homes and practice physical distancing. This order placed temporary restrictions on dine-in restaurants, bars, gyms, and retail stores, and ordered non-essential businesses to cease operations that required in-person attendance.

The stringent stay-at-home orders imposed to mitigate the spread of coronavirus quickly caused an unprecedented rise in unemployment. In April, the U.S. unemployment rate reached 14.5 percent, the highest level since the Great Depression. Despite numbers soaring across racial and ethnic lines, researchers found that the coronavirus pandemic has affected people of color at disproportionately higher rates. Their analysis revealed that while White people had an unemployment rate of 12.8 percent, the unemployment rate for Black people was 16.6 percent and 18.2 percent for the Latinx community. This data is not surprising, as we have historically seen that when the economy is flourishing for the elite, the labor market for minorities remains unsteady and even more dangerous during economic downturns. In the U.S., Latin American immigrants remain overrepresented in blue-collar, low-wage agricultural, domestic, and vocational jobs with minimal job security, which put them at higher risk for contracting the virus and getting laid off. For undocumented workers, financial insecurities are exacerbated because they are unable to qualify for unemployment.

The loss of jobs has not only affected workers and their families in the U.S. but also their relatives in their countries of origin. Although Lilian is an essential worker and remains employed, her weekly shifts have been reduced by more than ten hours. Now, she worries about how she will pay for food, rent, utilities, medicine, and accumulated debt while still being able to send money to family in El Salvador. The World Bank projects that the COVID-19 pandemic will cause remittances worldwide to drop about 20 percent in 2020, “the sharpest decline in recent history.” This decline could have long-lasting effects on the economy of receiving countries.

Immigrants have been remitting to their countries of origin for years. Their reasons are usually to invest in material assets, build social and financial capital in case of a return, and financially support the family unit. In El Salvador and Honduras, for example, remittances represent approximately 20 percent of each country’s GDP. Indeed, about 20 to 35 percent of Salvadoran nationals emigrate, and the money that they send is often a financial lifeline that keeps loved ones out of poverty. The Salvadoran diaspora has become such a “valuable commodity” in the country because its remittances are an important pillar in maintaining the national economy. In her book on transnational immigrant families, sociologist and Central American scholar Leisy Abrego demonstrates that the money sent to families helps decrease poverty and inequality, increases access to education, and provides support to the retired elderly. Households that receive remittances are also more likely to have access to basic services like running water and electricity.

The process of remitting is more than just an economic transaction, it is also associated with the emotional and social processes that allow immigrants to stay connected to the ancestral homeland. For Central Americans, migrating North has not been an easy journey. Central Americans have been fleeing the economic, social, and political unrest caused by U.S-fueled civil wars and genocide, multinational corporate plundering, and corrupt governments. Once they establish themselves in the U.S, remitting becomes a way to show love, care, commitment, sacrifice, and to reassure family members that they are not forgotten. Providing financial assistance is also viewed as a sign of “making it,” and, unfortunately, many may even think that the long-term family separation and the psychological trauma is worth it.

The coronavirus, however, has completely destabilized remittance patterns. Families, whose incomes have been affected, now feel powerless because they are struggling to support their relatives who are suffering from multiple pandemics (such coronavirus and social control from the government). Instead of sending money once or twice a month, they now send smaller amounts or even none. Indeed, this was reflected in El Salvador during the month of April, when remittances drastically dropped by 40 percent from the same month as last year. The Salvadoran Ministry of Economy quickly took action and announced that Salvadorans abroad could send their remittances at zero cost or at a discounted rate to their families in El Salvador. The country had to resort to “quick and innovative ways” to incentivize families to keep sending money.

Four months have passed since Mayor Garcetti launched the “Safer at Home” order in Los Angeles, but COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations continue to rise. In the first week of July, there have been more than 1,400 positive cases in the Westlake District, the home of Lilian and a historically Central American immigrant community. The streets of Westlake have been decorated with A-Frame signs to warn residents that their neighborhood is a high-risk area. Nevertheless, even if people wanted to stay home and practice physical distancing, they couldn’t because most Westlake residents are essential workers. These precarious work environments, along with health disparities and rising unemployment rates, have made two major things very clear to me: 1) the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated and magnified the structural inequalities that affect working-class people of color, and 2) Latin American immigrants are facing the consequences of our government’s failure to combat COVID-19 at disproportionately higher rates. We cannot afford to continue ignoring the warnings by public health experts nor dismissing the realities of immigrant families and their struggle for survival. We must realize that our actions have transnational implications that will have a long-lasting effect on remittance patterns that will directly affect the well-being of millions of people in Central America and around the world.

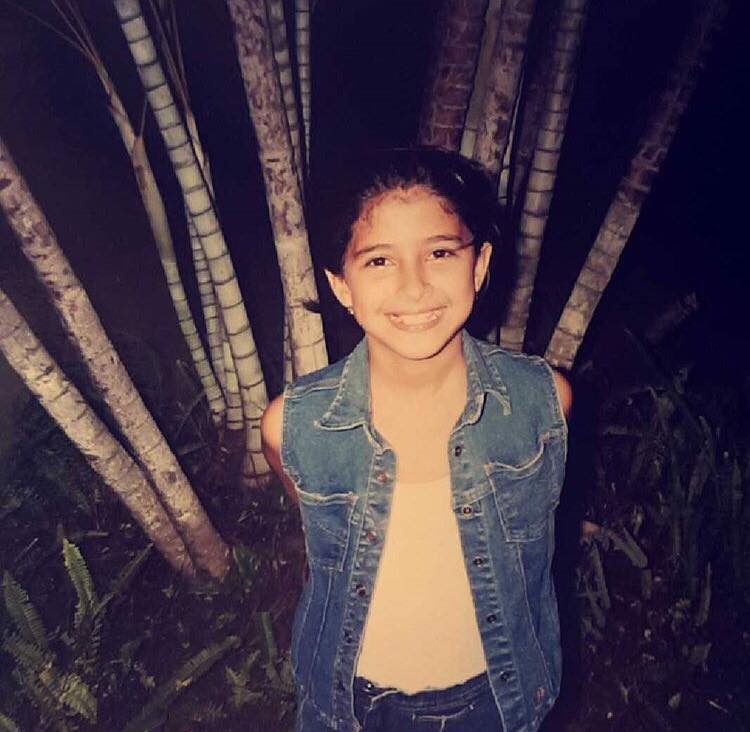

Adriana Cerón (she/her) recently graduated from Pitzer College with a BA in sociology and a minor in Chicano/a-Latino/a Studies. She is a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow interested in the integration, attainment, and mobility of Latinos in the U.S., with a particular focus on U.S. Central Americans. Adriana was born in El Salvador and at the age of five migrated to Los Angeles, CA, where she has lived since.